After watching the documentary Rivers and Tides, I really fell in love with the work of Andy Goldsworthy. His work is beautiful in its simplicity and love of nature. He becomes one with his landscape and gives each work to nature as a gift. He works only with his hands no matter the temperatures he encounters. His works range in materials such as flowers, twigs, stone, leaves, ice and many other mediums. This is interesting to note because his work is always in a new site with materials used from only the area he is working with that day. He also learns a lot about a place from observing it and reacting to it through art. Below I have answered some questions in regards to the film and his work as a whole.

Why does Goldsworthy resist the label of Greenbergian Formalism? On what basis, if any, might Clement Greenberg resist Goldsworthy’s work?

I think that Goldsworthy resists the label of Formalist because he sees himself as one with nature, not someone who works with strict artistic rules. I believe he is not a formalist, rather a land artist with formalist ideas. Meaning that he works within nature, but does have rules that he holds himself to while working. When making a work, he must only use materials found in that landscape and once finished the land will destroy it in such a way that it adds to the piece. I think that Clement Greenberg would absolutely resist Goldsworthy’s work because while his work has rules it is not work that can be seen regularly by the public to view. Greenberg believes that work should be viewed by the public to learn from, not be an intimate conversation between artist and nature, where photographs are the only evidence it exists.

Assuming Greenberg is not the most sympathetic to Goldsworthy, which among other Formalist traditions would be a better match, if any: a Kantian-Hegelian pre-Modern viewpoint, a Bellian early-Modern “significant form” criterion, or a Structuralist post-Greenbergian analysis? Defend your choice through comparison.

I think that Goldsworthy would fit much better into the category of Structuralist post-Greenberg. This is due to the fact that Goldsworthy uses the structures of nature to create his works while celebrating nature as a whole. He uses his land art to point to greater issues that can lead to conversations about nature. Joel Shapiro is a structuralist like Goldsworthy except for the fact that he works with manmade materials. They both use raw materials and push it to its absolute limits. Even Agnes Martin is like Goldsworthy in a way with her differences to other painters in her field. Goldsworthy is really like no other and can be hard to pin point others like him in the artworld.

Month: October 2015

Animation Lineage

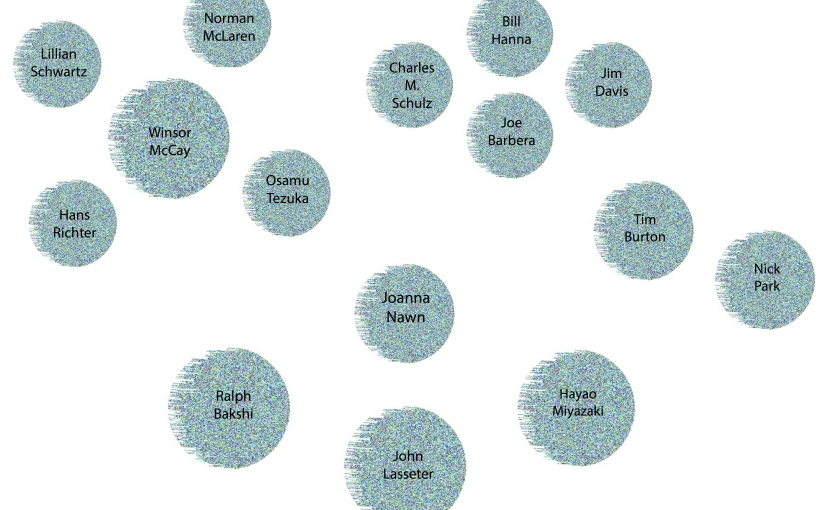

My work resides in the animation industry where many influential figureheads have paved the way for the future of the industry. Since animation is such a specialized field I will explain how each member of the diagram has influenced animation as a whole. First I want to explain why I want to be a part of this industry.

I have grown up watching these animators work and have fallen in love with the people who have created the work. I want to bring inspiration to others as they have done so for me. Animation and digital arts are my passion and the people I will be discussing are the many people that I take inspiration from and hope to be among them some day. There is just something beautiful about creating something so realistic that your audience is transported into to that world. I see the work of John Lasseter and I think to myself, how can one person think of so many amazing movies that make everyone love them so much. I dream of my work one day inspiring others as John Lasseter’s work does.

Now everyone thinks that animation did not start until Walt Disney, but that is false. Let’s start with the grandfather of animation, Winsor McCay. He first started out as a newspaper comic strip artist then later became an animator. He is best known for his animated short Gertie the Dinosaur. He made animation popular with audiences for the first time, which paved the way for everyone else in the animation industry. We then move to Norman McLauren a Canadian animator who created the widespread usage of animation techniques that were pivotal to the development of the industry. Without these two men animation might not have developed the way it did, which is very important to note. Next I will discuss two artists that works developed the industry even further.

The two artists that shaped the animation industry are Lillian Schwartz and Hans Richter. Hans Richter was a German painter that later created film. He is credited for making one of the first abstract films, which is a pretty big deal. We also recognize Lillian Schwartz as a contributor to animation because she was one of the first artists to use computerized media in art during the 1960s-70s. This was during a time when using computerized media was not the norm. Some of the techniques she used in her art would soon become commonly used in softwares like Photoshop. Although Photoshop is not animation, the development of software is important to the industry because the more advanced are made the better they can be utilized in other softwares. Artists have always pushed culture and media forward but so have these next few artists I will discuss.

We now move to better known figureheads that helped to shape animation as a whole. Osamu Tezuka is one of these huge influences to the animation industry with his work on Astro Boy. He also created the infamous large eyes featured in every Japanese anime. Although he may not sound like a big deal, he is due to his moving of comic characters into a television format. One really well known man is Walt Disney, who really made animated films worthwhile for audiences, namely families to enjoy. He and his Nine Old Men, another name for his nine main animators at the Disney Animation Studios, worked on the films we all grew up watching as children. Two of these Nine Old Men, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, are to this day hailed for their book Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life due to it containing the twelve basic principles of animation. These basic principles still hold true today even though we work digitally now. Their work was revolutionary and is still used to help others learn the field of animation today.

Now keeping with the theme of childhood animated shows everyone remembers Scooby Doo. The co-creators of the Hanna-Barbera Studios, Bill Hanna and Joseph Barbera, made the most popular animated tv shows to date. The made animated TV shows a household tradition that would be passed down to future generations. I wouldn’t leave out Charles M. Schulz and Jim Davis everyone loves Peanuts and Garfield especially due to how hard it was to get work published during that time.

Now there are two men to mention even though their work was not digital nor drawn. They are Nick Park and Tim Burton. They worked in animation, but mainly clay animation and drew in their own popularity. Nick Park is best known for Chicken Run and Shaun the Sheep along with others. Tim Burton is known for his live action films as well as A Nightmare Before Christmas and James and the Giant Peach. The last three men mentioned have done so much for industry.

The last three men I will mention are very respected today and have achieved greatness in the industry. First I will talk about Ralph Bakshi who is mostly know for his work as a director of animated and live action films. He created his own studio, Bakshi Productions, after working for Paramount Pictures. He is credited for creating the first x rated film Fritz the Cat. He has also worked on The Lord of the Rings and Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures. The second man Hayao Miyazaki is one of the most inspirational people in the industry to date since Walt Disney. He is actually referred to as the Japanese Walt Disney and with good reason. He has worked as an director, animator, manga artist and many more. He also is the co-creator of Studio Ghibli which has produced many popular animated films such as Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro and Howls Moving Castle just to name a few. Many animators and artists in general look up to him including animator John Lasseter. He is one of the biggest names in animation, especially after the creation of Pixar. He is the mastermind behind almost if not all the Pixar stories shown on screen.

All of these people have changed the way we watch film and serve as inspiration for me on a daily basis. I love knowing that the potential for great films is reachable and I hope to one day make an impression on the world with my work.

Mondrian Animation

This project was created for my Art 314 Modeling and Animation class. I was tasked with picking a Piet Mondrian painting, creating the shapes and animating those shapes to form the original painting. This project was created through Maya 2016.

Intent versus Content

Intent versus content is a major concern in the art community. Is it the artist’s job to give spectators their intent for a work or is it the spectator’s job to research what the artist had intended? The debate goes both ways depending on whom you ask. I personally believe that it is the spectator’s job to research the artist’s intent and then interpret the piece through the viewpoint of your life experience. The quote below is by Marcel Duchamp and he explains the unique relationship between the artist and the spectator.

“The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.” – Marcel Duchamp

What should an artist do when the spectator creates entirely unexpected expressive or cognitive content for a work? Should that matter to the artist?

As Duchamp’s quote suggests, the spectator brings the work into an artworld that is equipped to interpret it. In my opinion, when a spectator reacts to a work in an unexpected way it gives the work more meaning. It also helps the artist understand the impact they have on people through their work. It can be a great experience to hear what spectators have interpreted from viewing your work. We as artists want to emotionally connect with spectators. When a spectator brings their life experiences to a work, it changes the intent for that individual and carries meaning for them.

Should the artist attempt to inform the spectator of his or her expressive or cognitive intention beforehand, say through some kind of artist’s statement? Does this stifle the spectator’s own active participation?

I believe that a work does not need an explanation of the artist’s intent. If a work has truly touched someone, it is his or her job as a spectator to go and find the background information on the work. This makes the work a complete give and take from artist to spectator, which is interactive and most likely emotional. A great example of this is Louise Bourgeois; her work might not make sense unless a spectator does the research on her life story. After understanding her struggles in life, you can then interpret the piece, making the work more emotional and personal for you as a spectator.

When, if ever, is a spectator’s knowledge of an artist’s intent for an artwork relevant to interpreting or judging the work? If you did not know the autobiographical details of the life of Louise Bourgeois, for example, how would you react to her work differently, if at all?

I believe that if a spectator is to interpret or judge a work they need to do some research on the artist’s intent. Knowing the backstory can really change a person’s perspective of a work; especially if it is has great emotional value to the artist. If I didn’t know the autobiographical details of Louise Bourgeois life I would not have the same emotional connection to her work. For me at least, Bourgeois’ work is heartbreakingly beautiful and I feel privileged to have had her share her deep emotional experience with the art community. Without knowing the details I would have thought she has a possible background in science and really liked spiders and observing them. I was way off with my assumption, but now knowing her life story her pieces mean so much more and are so emotional for me.